In our previous blog post, we discussed the external trends affecting patent value, including macroeconomics, business trends, technology trends, legal and regulatory changes, and geopolitical trends. In this post, we will delve into the value of a patent portfolio – that is, a collection of patents marketed together.

A patent portfolio can range from just a few patents to thousands. The patents within the portfolio can either reinforce each other, increasing its value, or they can detract from the portfolio’s value.

Value in Numbers

A patent portfolio can have greater value than the sum of constituent patents’ values.

With enough effort and expense, it is often possible to invalidate a single patent. And once invalidated, a patent has no value. However, invalidating every patent in a large portfolio is nearly impossible and would be prohibitively expensive. Potential buyers can be confident that a good proportion of the patents will remain valid even after a concerted legal attack.

The larger the portfolio, the harder it is for competitors to avoid patent infringement. To avoid infringing one patent, it is often possible to redesign a product. However, it is much harder to avoid infringing all the claims in a large patent portfolio. A redesign to avoid one claim can cause a product to infringe a different patent claim. This is a so-called “patent thicket”.

In other words, a large patent portfolio has diversity and redundancy, making it much more robust and more valuable to sell.

However, diversity and redundancy only emerge when a portfolio has coherence: the patents must address related technical problems or product types. If a portfolio does not have coherence, when selling the portfolio, it is better to split it into smaller, more coherent portfolios. In our experience, portfolios ranging from 10 to 1000 patents are generally easiest to sell.

Portfolio Hierarchy

With many patents in a portfolio, how do you make sense of them all? It is unlikely that you have time to read and understand every patent.

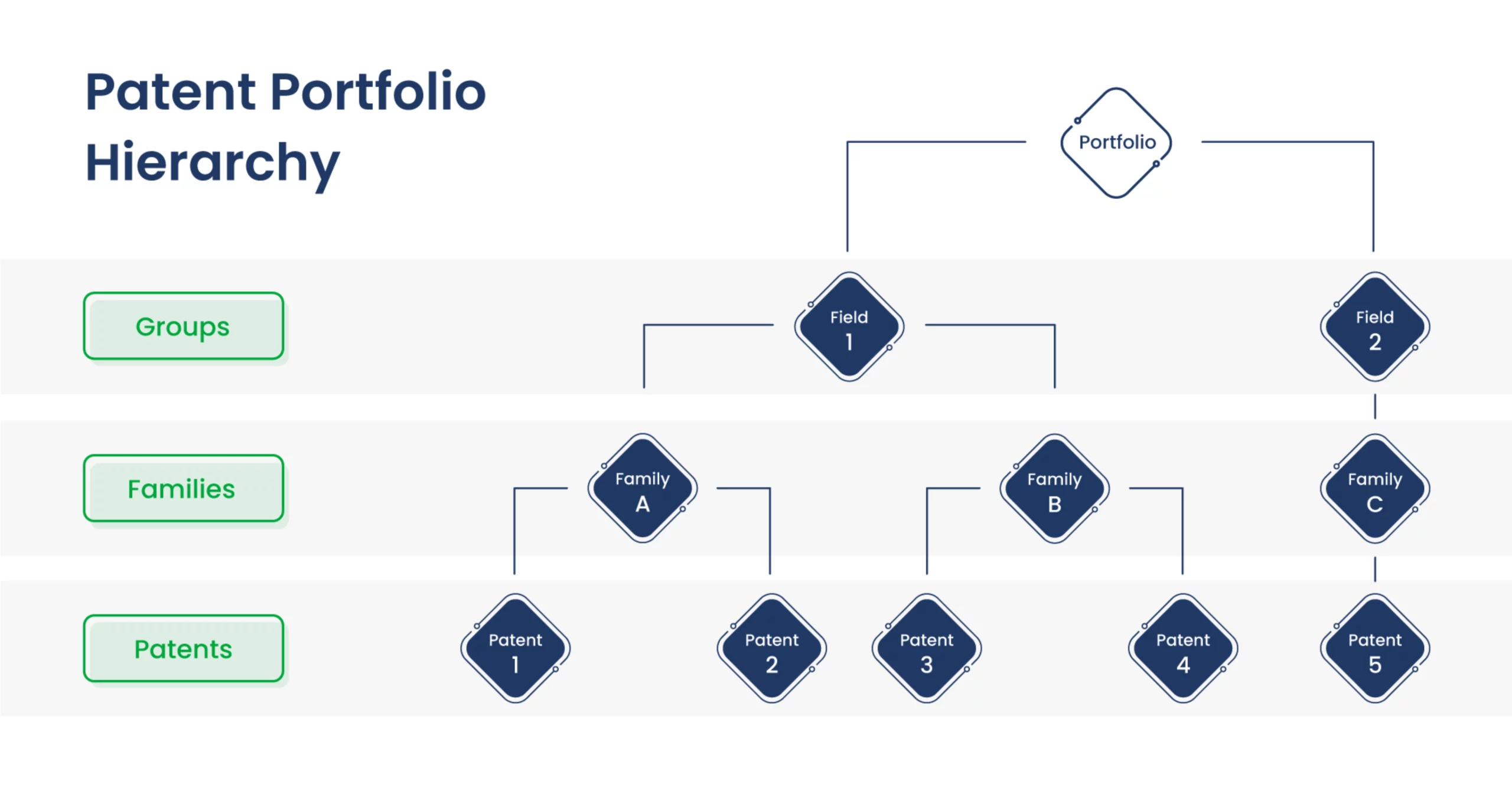

When selling or licensing patent portfolios, we make the portfolio easier to understand by organizing the patents into a hierarchy:

- Grouping patents by field provides insight into their likely use and allows buyers to focus on areas of interest.

- Identify patent families.

- Identify the best patents and their best claims.

Grouping patents by field provides insight into their likely use and allows buyers to focus on areas of interest.

A patent family consists of all patents originating from one original application (the “priority application”). A family may include multiple patents from one country and foreign counterparts from multiple countries. Since the different members of a patent family contain much duplicated information, by grouping the patents into families, you can help the reader avoid reading duplicate information and just focus on the differences within the family. As an aside, when buying or selling a patent, all family members should be included in the transaction.

Identify the Best Patents and Claims

Identifying the best patents and claims within a portfolio is a complex process, which we will address in a subsequent blog.

Geographical Scope

Having patents from different countries adds value to a portfolio. Differences in patent law between countries also provide diverse options for using patents.

For example, in the US, it can be difficult to obtain an injunction against an alleged infringing product, but courts can award high damages. By contrast, in China, obtaining a temporary injunction is relatively easy, but liquidated damages awards are relatively low. Thus, a patent owner can use US and Chinese patents to complement each other. Use the Chinese patents to obtain an injunction to bring the other party to the negotiating table; use the US patents to increase the value the portfolio.

In which countries should you obtain patents? There is a tradeoff between cost and breadth of protection. In the information and communication technologies (ICT) industries, products are complex and potentially covered by thousands of relevant patents. Companies usually obtain patents in just a few jurisdictions, mainly the US, Europe, and China, major markets for products and the major manufacturing locations.

In the biological, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals (BCP) industries, just one patent family or a few patent families can define a valuable product. Companies can apply for relatively few patent families, but they obtain foreign counterparts in many countries. Other industries fall between the extremes of the ICT and BCP industries.

Granted Patents and Pending Applications

Granted, active, valid patents provide legal protection. A portfolio needs at least some granted patents in major jurisdictions such as the US, Europe, or China to have value.

Pending applications have potential for providing future legal protection, but do not yet provide legal protection because they could be rejected or could require modification before being granted. Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applications give applicants the right to make patent applications in individual countries or regions, but do not provide legal protection of products. Therefore, a portfolio with only pending applications rarely has value.

However, having both granted patents and pending applications in a portfolio has value. Granted patents define current intellectual property rights while pending applications allow for modifying claims or filing new claims to reflect recent technological trends. A portfolio with both granted patents and pending applications is potentially more valuable than one with only granted patents.

Ownership, Encumbrances, and Existing Licenses

Incorrect recording of patent ownership is surprisingly common. Each time a patent changes hands or the owner’s name changes, an assignment document should be registered with the national patent office. A mistake in any of the assignment registrations can affect the entire chain of title and make ownership unclear. This can take time and expense to correct. In some cases, it can render the patent worthless.

Patents can also be subject to existing licenses. Understanding and documenting existing licenses is essential – if patents are already licensed to key competitors, and particularly if a license grants sub-license rights to third parties, the patents’ value may be diminished or even zero. Patents may also be subject to other encumbrances, such as being pledged as security for a loan. It is almost always necessary to discharge any such encumbrances before selling a patent.

Commercial Use

Many patents have no sale or licensing value, while others have very high value. Commercial use determines patent value. For a portfolio to have value, at least some of its patents must be in current or imminent use by a commercial product. And the market for those products should be large – our rule of thumb is annual worldwide revenues of at least $100m.

To convince others of a patent’s sale or licensing value, it is necessary to provide evidence of its use by commercial products. For some combinations of products and patents, this is easy to prepare, but for others it can be extremely difficult and expensive. If you cannot provide evidence of use, it is hard to sell or license a patent.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we’ve discussed the factors that affect a patent portfolio’s value: the number of granted patents and applications, portfolio hierarchy, best patent claims, geographical scope, ownership, licenses, and commercial use. In a subsequent post, we’ll delve into the value of individual patents and patent claims.